-

A Hellish Noise, 2015

21 mins

Screenplay, editing: Tatiana Lecomte

Camera, sound: Robert Schabus

With Julien Baissat and Jean-Jacques Boijentin

Production: Tatiana Lecomte

Commissioned by the Bundesimmobiliengesellschaft

In French with English subtitles

Colour, 16:9 -

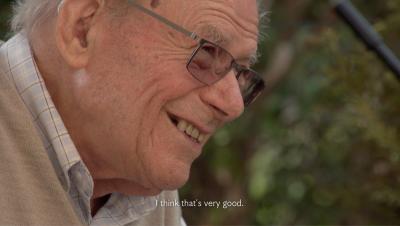

Eye-witness Jean-Jacques Boijentin with foley artist Julien Baissat on set, 2014

Rolf Wienkötter

Insofar as it relates to the crimes of the Nazi era, the culture of commemoration is currently in a critical phase. Soon we will have to go without eyewitnesses capable of entering into a dialogue with younger generations based on their own experiences. Individual narratives of suffering will only be available in categorised, museum-processed form. Keeping memories alive is a historical, political and moral imperative. Finding ways to achieve this today and in the future is a challenging issue, and still unresolved.

This issue has accompanied the artistic production of Tatiana Lecomte for some time. She views existing methods of processing the past with scepticism. The 'strong image', the 'authentic setting' and 'decisive documentation' remain areas of hope for one representation of history intended to engage those born later. So too, the account by one person who experienced those terrible events and survived is intended to engage people with occurrences that are receding deeper into the past.

Jean-Jacques Boijentin is such a person. Born in 1920 in Rouen, in the North of France, he lived as a mechanic in the rural town of Mussidan in the Dordogne. On 16 January 1944 the village was surrounded by the Gestapo and the Milice in retaliation for the shooting of a Vichy spy by the French Resistance. 36 people were arrested, among them Jean-Jacques Boijentin and his father Maurice. They were taken to the Compiègne internment camp north of Paris, and subsequently deported to Buchenwald concentration camp, then to Mauthausen, and ultimately to Gusen in Upper Austria on 11 March 1944. Maurice Boijentin was murdered in Gusen; Jean-Jacques lived to see the liberation by American troops on 5 May 1945 in Mauthausen, and was able to return home to Mussidan. After the war he chaired a society providing support for homecoming concentration camp inmates, and was active until his retirement as an electrician, a film projectionist and the owner of two firework shops. He now lives in a home for senior citizens in the Dordogne.

Gusen concentration camp in St. Georgen an der Gusen (East of Linz) was a satellite camp of Mauthausen concentration camp. Under the codename B8 Bergkristall, prisoners were forced to work on the construction of a secret underground factory for Messerschmitt jet fighter planes. Conditions in the camp were inhuman and working conditions during the day even worse. Jean-Jacques Boijentin worked in the tunnel. His experiences provide the basis for Lecomte's film.

The structure that is accessible to the public today gives no impression of conditions at the time. The artist was particularly struck by the silence. Eyewitnesses talk about the unbearable noise of the heavy machinery employed in the construction of the tunnels. Lecomte sets out to capture this noise on film.

To this end the film moves far from the scene of terror to visit Monsieur Boijentin in France. A second person joins them, a young man called Julien Baissat. The normal allocation of roles — the eyewitness speaking while somebody else listens with understanding — is dispensed with in favour of a working situation where both parties are contributing their own experiences and their own knowledge. Preoccupation predominates over emotional responses, allowing a certain distance to the awfulness of the scenario they are recreating. The reduction to one aspect of the whole situation for the senses shifts the perspective: Memories appear as the action, as a working process, as something to be given a final manifestation, although it is one that always falls short in engaging with what happened. At the same time the artist provides a means of expression beyond words, which invariably rob the unspeakable of its intensity.

Tatiana Lecomte leaves out much of what we generally think of under the heading of 'Commemoration'. Her approach creates an awareness of the sense in and limitations of remembrance without losing sight of the terrible events being remembered. She does not deliver final images but suggests, instead, that we should never cease to make our own picture.

(translated by Jonathan Quinn)

-

Jean-Jacques Boijentin (1920 - 2015)